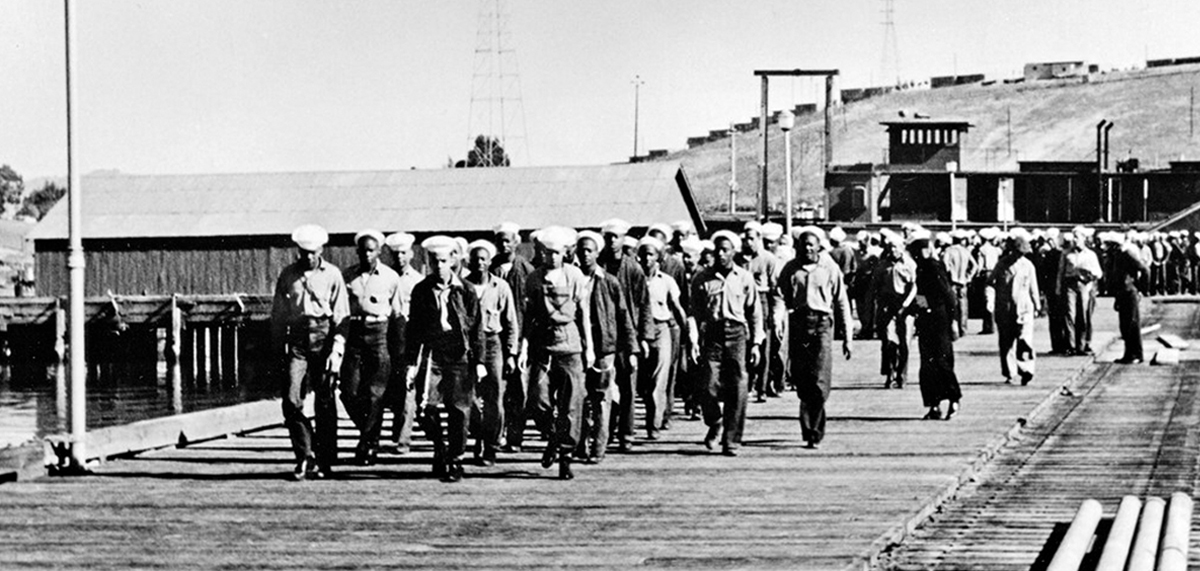

During World War II, nearly a million Black Americans served in the U.S. Armed Forces, but the military at that time was racially segregated, and Black servicemen in the Navy were restricted to non-combat assignments. These assignments were usually the least desirable duties deemed unfit for White sailors, which ranged from menial tasks to the most back-breaking work. At Port Chicago Naval Magazine near Concord, California, newly-arriving Black sailors hoped to serve at sea and engage in combat, but quickly learned their duties would be limited to the arduous and hazardous task of loading ammunition and explosives into Navy ships.

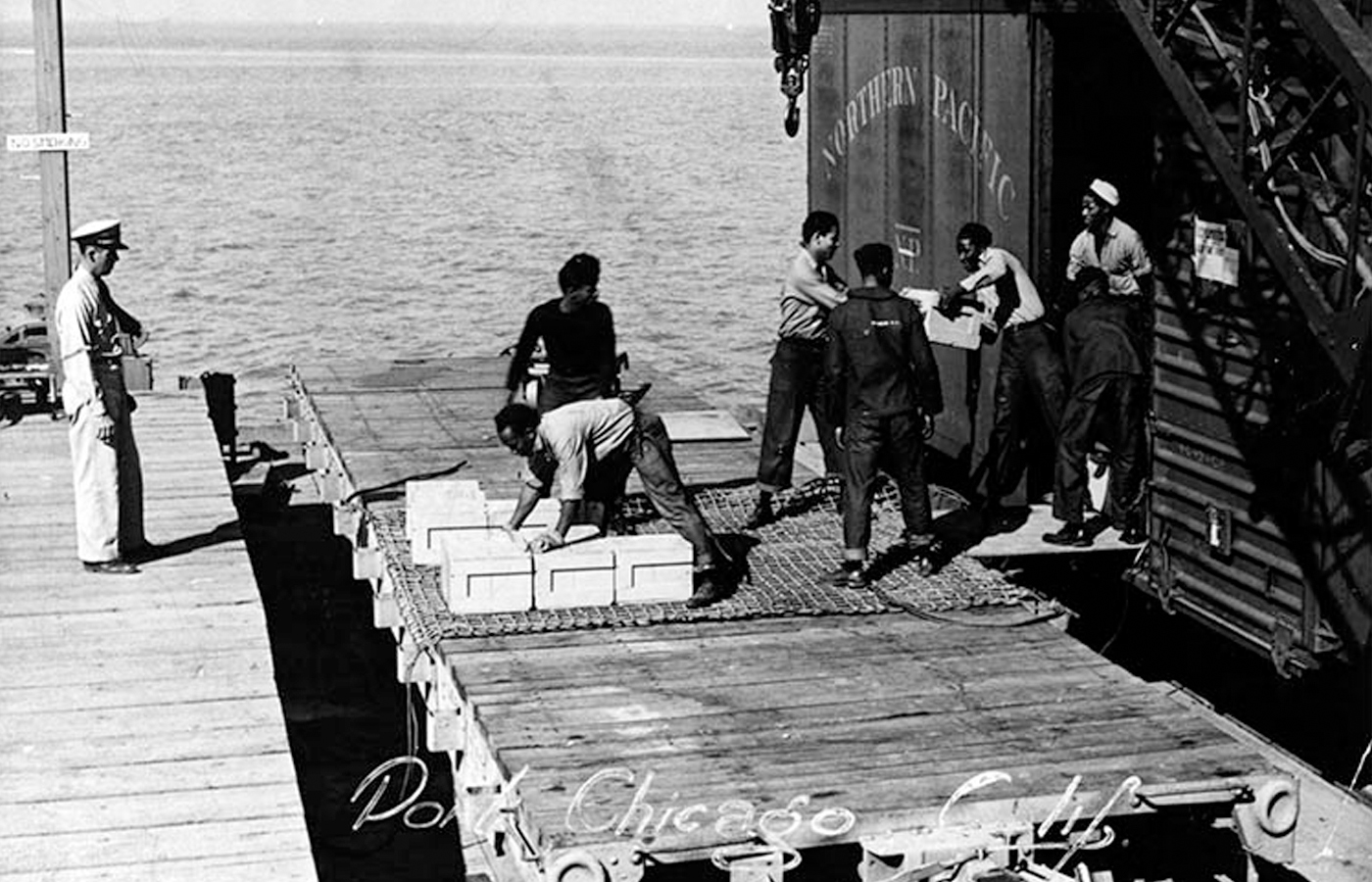

The naval base was racially segregated, so the commanding officers at Port Chicago were all White and the sailors loading were all Black. The work was grueling, and Jim Crow segregation policies were strictly enforced. For example, Black sailors were prohibited from using the "Whites Only" restrooms aboard the ships they were loading, so they were made to walk a half-mile to use the restroom.

Although loading bombs and explosives is extremely dangerous work, the Navy neglected to provide the sailors with adequate resources to safely carry out their duties. The sailors were not given specialized training in handling explosives. Basic gear like gloves to grip the grease-slathered bombs were not provided. Sailors who looked to officers for guidance on safest methods for carrying explosives were erroneously told the munitions could not explode because they had no fuses or detonators.

Ships were loaded non-stop, 24 hours a day with sailors working in three 8-hour shifts. Commanders at Port Chicago wanted the ships loaded as quickly as possible, and following Naval safety regulations was seen as an impediment that slowed production. As a result, federally-mandated safety codes were intentionally ignored. Sailors lifted live bombs by hand and were encouraged to roll heavier bombs along the dock. Powered winches were used to lift heavy loads, and although the machinery was often in disrepair — with broken levers, valves, and even brakes — sailors were instructed to load these devices beyond their weight capacity to speed up the process. Naval officers also raced divisions of sailors against each other, betting on which group could load explosives the fastest.

Practices that prioritized speed over safety led to a dangerous working environment at Port Chicago, and many sailors felt the working conditions were unacceptable. Actor, singer, and civil rights icon Harry Belafonte, who served briefly at Port Chicago in 1944, wrote in 2011 about the dangers of loading munitions:

- "Not only was this menial work, it was incredibly dangerous, the more so because none of us had had any training for it. We knew exactly why we'd been chosen. This was scut work for the lowliest and most expendable Sailors in the U.S. Navy: the black ones."

Policies and practices of racial segregation at Port Chicago not only contributed to unsafe conditions, but fostered low morale amongst the enlisted men. Many of the Black sailors at Port Chicago successfully completed naval rating exams in training schools or during basic training which qualified them for specific trades like machinist's mate, gunner's mate, aviation metal smith, store keeper, quartermaster radioman, and diesel expert among others. Initially, the sailors believed if they worked diligently and exhibited exemplary behavior, they could be promoted in rank to advance to their eligible occupational specialty. Port Chicago leadership, however, remained unwavering in their decision to assign Black sailors by race rather than merit, denying them opportunities for advancement and wage increases.

"I came out of this school and made gunner's mate third class," recalled Sailor Cyril Sheppard, one of the fifty sailors known as the Port Chicago 50. "I had the highest marks. But I never did wear the stripe. All they knew was that I was just another sailor... And I resented it, too, because I went to school for gunnery. I didn’t come to do stevedore work... [and] they didn’t have the White men doing that stevedore work."

Several sailors requested change of assignment and asked to be transferred, while others filed complaints with the Navy about unsafe procedures. Complaints and requests were ignored or denied.

In a 1943 letter to a local attorney asking for assistance, a group of Port Chicago sailors wrote that their morale had dropped to "an alarming depth." They wrote: "We, the Negro sailors of the Naval Enlisted Barracks of Port Chicago, California, are waiting for a new deal. Will we wait in vain?"

The Port Chicago Disaster

On the night of July 17, 1944, two Liberty ships, the SS Quinault Victory and SS E.A. Bryan, were being loaded with explosive incendiary bombs, depth charges, and ammunition. At 10:18pm, two massive explosions at the docks, just seconds apart, lit up the sky. Fiery debris and chunks of metal rained down on the base and surrounding areas. Smoke and fire extended nearly two miles into the air.

The explosions instantly killed everyone within 1000 feet, including 320 servicemen, merchant marines, and civilian contractors. All those loading munitions at the time of the explosion were Black Americans, accounting for almost two thirds of the dead and amounting to 15% of all Black American military deaths during World War II. 390 civilians and military personnel were injured, many seriously. The Naval Magazine was completely destroyed. It was the deadliest home front disaster of World War II.

The explosions caused severe structural damage in the nearby town of Port Chicago and broke windows in surrounding communities, with the impact being felt as far away as Nevada.

Port Chicago Sailor Robert Routh reflected on the sudden and devastating loss of so many of his fellow Sailors. "These were the kind of young Blacks that made the conditions tolerable because of their attitude and ready to joke and make you glad to be alive. And now to know that in three to four seconds their lives were just snuffed out... There was nothing said about this, the tragic loss of life. Where was the reporters then, writing about that?"

Many of the surviving Black sailors were off-duty that night, preparing for bed in their barracks when the blast occurred. As windows shattered and the barracks roof collapsed, dozens were injured. In the midst of the tragedy and chaos, hundreds of surviving Black Sailors responded with exceptional courage, going beyond the call of duty to assist the injured and contain the damage caused by the explosions.

Sailor Percy Robinson recalled, "When I got outside [the barracks], there were a few people outside yelling for volunteers to go down to the docks. I went up to the guy and said, 'Hey, I want to volunteer.' He asked me, 'Did you see Percy get out of the barracks?' He didn't recognize me, he was my squad leader, because my face was so mutilated from the blood and guts.'

The surviving Black sailors played vital roles in rescue operations during the emergency, most notably in extinguishing fires near boxcars filled with explosives, effectively averting another massive explosion. Afterward, the Navy commended some 200 Black sailors for volunteering with "coolness and bravery" to assist during the rescue. The Admiral of the Twelfth Navy Division proclaimed, "As real Navy men, they simply carried on in the crisis attendant on the explosion in accordance with our Service's highest traditions."

When sailors have been through an ammunition explosion or serious accident, it is usually naval policy to assign them to shore duty or a complete change of location and duties. However, in the days that followed, many of the surviving injured Black sailors, still shaken from the traumatic event, were tasked with cleaning up the remnants of the disaster, including the body parts of their compatriots. Port Chicago 50 Sailor Jack Crittenden described the traumatic experience:

- "It was a sight that you don't want to talk about. Arm here, leg here, head here, a shoe with a foot in it. This is on the water and on the ground and, oh man. Awful."

Meanwhile, as the Black sailors were made to cleanup the grisly scene, their White counterparts were granted a 30-day survivor's leave to return home, heal from their wounds, and visit family and loved ones. Black sailors were never granted such a leave.

The Port Chicago Protest

Within days after the gruesome cleanup, with the war raging on and our troops still needing munitions overseas, the sailors were sent to Mare Island Naval Ammunition Depot about 25 miles from Port Chicago in Vallejo, California. With divisions depleted from the deadly disaster, the surviving sailors were joined by new crews of inexperienced young men. The Navy's investigation into the cause of the disaster was not yet complete, so sailors and commanding officers did not know what precautions to take in order to prevent another disaster. The sailors would be serving under the same leadership responsible for previous safety violations and there would be no changes to procedures, conditions, or safety practices.

On August 9, 1944, when 328 sailors were directed to march toward the ships to load munitions, the sailors all stopped in their tracks. When asked if they would resume handling explosives, the majority of them objected. Some sailors found themselves too traumatized from the events to continue working with explosives. Others wanted their safety concerns addressed, or wanted to be assigned to alternate duties. Still others were tormented by the unequal treatment between White sailors who were granted leave and Black sailors who were made to clean up body parts after the explosions. What united them all was their shared aspiration to have their lives valued the same as the White sailors who were being safeguarded from the mortal dangers of loading munitions.

The sailors' conduct records up to this point had been perfect. When asked individually if they would follow orders to load, about 70 of the sailors agreed to return to loading duties. The remaining sailors explained to the officers they would serve their country performing other duties, they'd accept transfers, or fight overseas in combat, but would not continue loading munitions under the same hazardous conditions and leadership. They wanted what was given to generations of White sailors in similar situations – an extended leave and reassignment to alternative locations and duties.

In response, the Admiral of the Twelfth Navy Division – the same Admiral who publicly commended these same sailors for bravery during the emergency – dismissed their pleas for reassignment and threatened the men with death-by-firing-squad:

- "They tell me that some of you men want to go to sea. I believe that is a goddamn lie! I don't believe any of you have enough guts to go to sea. I have a healthy respect for ammunition; anybody who doesn't is crazy. But I want to remind you men that mutinous conduct in time of war carries the death sentence, and the hazards of facing a firing squad are far greater than the hazards of handling ammunition."

Rather than provide training to the sailors, bring working conditions up to legal code, or reassign White sailors to loading duties, Naval leadership packed 258 of the Black sailors onto a prison barge and threatened them with execution if they did not return to loading munitions.

The sailors remained on the cramped barge for nearly three days. Sailor Jack Crittenden described how military personnel tried to coerce and manipulate a statement from him:

- "I was down there in the stockade and they put handcuffs on me and carried me up to where it's not a stockade. This is where I'm being interviewed, and outside is a Marine. And if you ain't very cooperative, they tell the Marine, 'Come in here.' That Marine come in there with that billy club... and he's standing there gritting his teeth and all. Put some fear in you. Then you're supposed to say, 'Yessir, that's right, yessir.'... Anyway, this guy he said, 'All I intend to do is to write down whatever you say. And I just want you to sign it.'... I started reading [what he transcribed] and said, 'I didn't say this... This changes my thought. This changes my statement.'"

Sailor William Banks similarly testified that he was instructed by an Ensign to "sign a document containing statements that were not true." When he voiced his protest, he was informed he had "no alternative but to sign."

One of the men on the barge being threatened with execution was Sailor Percy Robinson, who explained:

-

“From my upbringing, my mother taught me that if a White man threatened to hang you he would do it at his first legal chance. And she told me about the Klan, and she was brought up in Mississippi. So I believed that they had a legal chance to shoot us. So I said, 'Well I'm not gonna give them a chance to shoot me. I'll go back to work.'"

After days on the overcrowded barge, 208 of the sailors, under extreme pressure and the threat of execution, reluctantly returned to handling explosives. However, even those who complied faced punishment; they would now be working under Navy command as unpaid laborers, as all 208 were court-martialed and deprived of three months' wages.

The prevailing sentiment among the remaining fifty sailors was that the disaster was primarily the result of hazardous working conditions and unsafe practices that required urgent attention. As a result of the disaster, the sailors now understood that Naval leadership had been untruthful when they claimed bombs could not explode due to the absence of fuses or detonators. They realized the Navy's decision to withhold safety code training had hindered their ability to report safety violations. Port Chicago command's prioritization of speed over safety, including betting on which division could load the fastest, now appeared to be gross negligence. Enlisting less-experienced sailors to assist them with loading, particularly before establishing a cause of the deadly disaster and implementing necessary improvements, appeared irresponsible. Considering these factors, returning to those conditions was deemed unacceptable, and underscored the injustice of assigning Black sailors exclusively to this perilous task.

Port Chicago Sailor Cyril Sheppard, who successfully passed exams qualifying him for the position of gunner's mate third class, said:

-

"Put me on a ship and let me fight out there. I'll take my chances there, but I don't want to see nobody lose their life on somebody else’s negligence."

Sailor Freddie Meeks later said the hazardous working conditions were his reason for not returning to the docks. "We said, if we are going to be shot, we will be shot. We were not going back to those conditions."

"This was my reason for refusing to go back to work –– to get the working conditions changed," said Sailor Joseph Small. "I realized that I had to work. I wasn't trying to shirk work. I don't think these other men were trying to shirk work. But to go back to work under the same conditions, with no improvements, no changes, the same group of officers that we had, was just –– we thought there was a better alternative, that's all."

Facing the very real threat of execution, fifty of the sailors, now known as the Port Chicago 50, stood firm and refused to continue loading munitions until the Navy changed their policies and practices.

For this, the fifty sailors were charged with mutiny.

Although the standard charge for disobeying an order is "insubordination," which carries a punishment of forfeiture of pay and dishonorable discharge, Port Chicago leadership pushed for a more severe charge of "mutiny" which carried a maximum wartime punishment of death.

The Navy's Court of Inquiry

A Naval Court of Inquiry, or official investigation, began on July 21 but wasn't completed until August 29, twenty days after the sailors were directed to return to loading munitions. As part of the investigation, three senior officers and a judge advocate interviewed 125 witnesses over a month, only five of whom were Black sailors.

The inquiry report found Port Chicago leadership had shown a "general failure to foresee and prepare for the tremendous increase in explosive shipments." It also cited leadership's "failure to provide an adequate number of competent petty officers or even personnel of petty officer caliber."

In regard to hazardous working conditions and practices on the base, the report confirmed leadership's "failure to assemble and train the officers and crew for their specialized duties prior to the time they were required for actual loading." In an incriminating report, the inquiry found Port Chicago leadership had violated safety code and regulations, encouraged competition, and promoted criminalized loading practices.

The facts and evidence included in the report validated the sailors' opinions that working conditions and practices needed to be improved before sending American sailors back to loading duties. However, as was standard practice, the facts and evidence of the report were interpreted by Navy captains and commanders in an "opinions" section. Although the report was unable to find evidence of a specific cause for the explosions, the "opinion" section of the inquiry theorized that if the explosions were caused by human error, it was likely caused by the deceased Black sailors themselves. Specifically, the opinion was the explosions were caused by "rough or careless handling by an individual or individuals," not any failures of leadership. To back this claim, Naval leadership included the racist myth that Black sailors were inherently inferior to White sailors, including the opinion that Black sailors were "neither temperamentally [nor] intellectually capable of handling high explosives."

The Naval inquiry's assertion regarding the incompetence of the Black sailors was directly contradicted by an internal document written by the Admiral of the Twelfth Navy Division in early August which stated: "Negro divisions have heretofore turned in a satisfactory record in the loading of ammunition. Their records of tons per man per day equal those of civilian stevedores in this area."

The Navy's final report ultimately absolved all White officers and commanders of wrongdoing. The inquiry report stated that the aforementioned illegal actions of Port Chicago command "were contrary to the Coast Guard shiploading regulations [but] were not dangerous and did not increase the hazards."

Although Port Chicago command was not punished, the report verified they had broken federal safety code, disregarded Coast Guard orders, ignored Port Director warnings, and violated Naval regulations. This rendered the "unsafe" working conditions at Port Chicago and Mare Island completely illegal. This information was the exact evidence the sailors needed to absolve themselves of wrongdoing, because officers are obligated not to issue unlawful orders, and it is not a crime to refuse an order that violates federal and Navy regulations. This information, however, was marked "Confidential" and was not disclosed to the sailors or the public.

In anticipation of the inquiry report's classified release on August 28, Navy Secretary James Forrestal, at the behest of the Admiral of the Twelfth Navy Division, wrote a private letter to President Roosevelt which included the proposal to end racial segregation at Port Chicago and Mare Island. This vital addendum was hand-written in the margin of the memorandum, with an acknowledgement that "No white enlisted personnel are performing similar work at the [Mare Island] Naval Munition Depot or the [Port Chicago] Naval Magazine." The Secretary noted that this fact could be interpreted as "discrimination against negroes," and so changes had to be made immediately, before the mutiny trial, in an attempt to avoid backlash for subjecting Black sailors to hazardous conditions from which White sailors were shielded.

- "To avoid any semblance of discrimination against negroes the Chief of the Bureau of Navy Personnel has authorized the procurement and training of one battalion of white enlisted men for Port Chicago and one for the Naval Ammunition Depot, Mare Island. Authority has also been granted to arrange necessary rotations."

Within days, the Navy had integrated loading assignments at Port Chicago and Mare Island specifically to deny any claims of "discrimination against negroes" that may arise before or during the public mutiny trial. This tactic was put to the test just two weeks later, when NAACP Chief Secretary Walter White wrote a letter to Secretary Forrestal regarding the injustice of race-based assignments at Port Chicago and Mare Island. The Navy countered by claiming that Mr. White was mistaken, making misleading assertions suggesting racial segregation had never occurred at Port Chicago and Mare Island.

- Negro and white personnel, Navy and civilian, are used indiscriminately. In the loading and handling of ammunition depots and mine depots... both Negro and white personnel are used at Hastings, Yorktown, Mare Island, and Port Chicago. The Department will never select any race for exclusive assignment to, or exemption from, hazardous duty.

The Navy's public denial of verified facts, particularly in anticipation of a military trial, would now be deemed "obstruction of justice." Concealing internal documents that confirmed race-based assignments was a deliberate attempt to sway both the mutiny trial and public opinion in favor of the Navy, severely undercutting the sailors' ability to prove their innocence.

Meanwhile, President Franklin Roosevelt was paying close attention to the events surrounding the Port Chicago disaster and protest. In response to reading Secretary Forrestal's private memorandum and the Navy's inquiry report, President Roosevelt sent a letter back to Secretary Forrestal recommending the Navy be lenient on the sailors who had returned to regular assignments after participating in the Port Chicago protest. The President's letter read:

- "It seems to me we should remember in the summary court martials of these 208 men that they were motivated by mass fear and that this was understandable. Their punishment should be nominal."

While President Roosevelt viewed the motives behind the sailors' civil disobedience as justifiable, the naval court would grant no leniency for the Port Chicago 50.

The Mutiny Trial

The mutiny trial commenced on September 14, 1944 at Treasure Island in the San Francisco Bay. It would be the largest mass mutiny trial in American history.

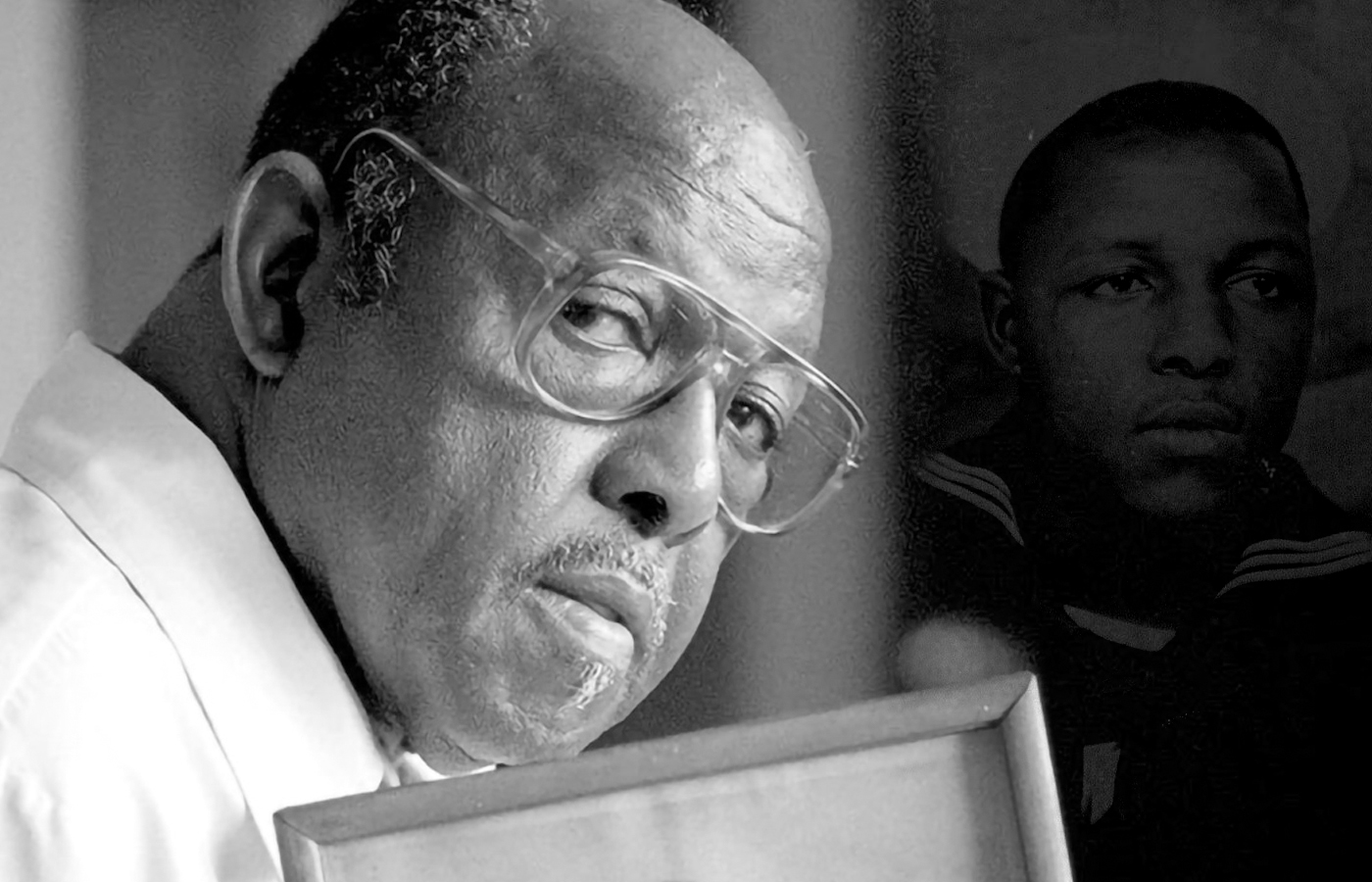

The U.S. military does not typically send public invitations to military trials, however the Navy made an exception in order to invite the national press to cover the mutiny trial. One member of the public attending the trial was future Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall, then a young civil rights lawyer for the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). Marshall observed the trial for 12 days and heard statements from each of the sailors. He declared the Navy was mishandling the case and was attempting to cover up its racist policies and blatant negligence by shifting blame for the disaster onto the Black sailors. He conveyed this to the national press, saying:

-

“This is not 50 men on trial for mutiny, this is the Navy on trial for its whole vicious policy toward Negroes."

Unfortunately, as a civilian lawyer, Marshall could not represent the sailors in a military trial. Marshall requested access to the naval documents and evidence that could have exonerated the sailors, but he was denied. In a statement to the Navy's Judge Advocate, he denounced the concealment of evidence, resenting the fact that, "I, as a civilian, cannot, under any circumstances I know of, investigate and yet the Navy can."

Military courts, distinct from their civilian counterparts, adhered to their own set of laws within the court-martial system. The trial took place before the enactment of the Uniform Code of Military Justice (1950) and Military Justice Act of 1968, and so the court proceedings lacked independence from the pressures and control of naval leadership. Consequently, there was no oversight to ensure the Navy's compliance with the U.S. Constitution's guarantee of due process of law. This absence of oversight left the sailors with no means to address the numerous violations of their constitutional protections. For example, the fifty sailors were denied the right to choose their own representation, and were deprived of individual counsel. Instead, the Navy appointed the sailors' attorneys for them, assigning five Naval attorneys to represent blocks of ten sailors each.

Additionally, the Navy-appointed defense attorneys were bound by rules imposed by naval command. They faced pressure to avoid witness testimony that could cast the Navy in a negative light during wartime. Consequently, evidence and testimony of hazardous conditions were prohibited, and sailors were instructed not to testify about topics such as racial discrimination, dangerous practices, or safety violations that could incriminate the Navy. These restrictive trial parameters left the sailors with very little recourse to prove their innocence, as their objections to loading munitions were rooted in the Navy's own shortcomings, including fostering hazardous working conditions, neglecting to train the sailors for their duties, refusal to follow federal laws and regulations, and a general disregard for the lives and safety of the Black sailors.

To secure leniency for the sailors and shield Naval leadership from scrutiny, defense attorneys focused their arguments on what President Roosevelt described as the sailors' “mass fear.” This mischaracterization undermined the sailors' legitimate concerns, shifting the focus from systemic failures to supposed individual weakness. Despite the lead officer testifying that only five of the sailors stated they were afraid to load munitions during the protest, all the sailors were portrayed as fearful, distracting from the real issue – the Navy's negligence and repeated disregard for the sailors' well-being. Reflecting on the trial, Sailor Freddie Meeks voiced his frustration: “We wasn’t allowed to say anything but what they would ask us.”

Thurgood Marshall similarly objected to the narrow scope of questioning and navy-imposed rules which restricted the sailors from testifying about the entirety of their emotions and circumstances:

-

"There are many factors involved in the working conditions in the Twelfth Naval District which could not be brought out at trial... The [defense counsel] did as fine as they could within the rules of the Navy, but they, of course, could not bring out other factors that, I submit, could have been brought out, such as background of the case, the background of what was in those men's minds."

As a result of the limited scope of questioning, the work stoppage – an act of protest which was a reaction to documented leadership failures – was portrayed as an unprovoked action prompted solely by the sailors' own cowardice. This "mass fear" defense largely placed the onus for the pivotal events at Port Chicago and Mare Island squarely on the Black sailors themselves.

The "mass fear" narrative also aligned with the prosecution's racist theories that Black sailors were inherently emotionally unstable, unintelligent, untrainable, mistake-prone, and cowardly. Thurgood Marshall publicly opposed the idea that Black sailors were unwilling to load munitions out of fear:

-

"Negroes are not afraid of anything any more than anyone else. Negroes in the Navy don't mind loading ammunition. They just want to know why they are the only ones doing the loading. They want to know why they are segregated; why they don’t get promoted."

Nevertheless, the trial devolved into a debate on whether fear was justification for objecting to orders, and whether the sailors were prepared and capable of carrying out their assignments. To this end, naval officers testified about the sailors' "inability to be trained" and "mishandling" of explosives. These two talking points appeared to directly address the Navy's determination that Port Chicago leadership itself was responsible for "failure to assemble and train the officers and crew for their specialized duties" including illegal loading practices ("mishandling") which were enforced by Port Chicago officers.

From a legal standpoint, this narrative insinuating that Black sailors were inherently incapable of handling munitions held little relevance in proving mutiny. It did, however, have the effect of publicly attributing responsibility for the Port Chicago disaster to the Black sailors rather than the Navy itself. This narrative exemplifies how sailors shouldered the burden of accountability for faithfully executing the misguided instructions of their superior officers.

Following weeks of court proceedings, evidence supporting mutiny was scant, as there was no attempt to usurp power, and the sailors adhered to all orders other than those related to loading munitions. The "mutiny" narrative was especially hard to maintain once officers testified that sailors were respectful and generally obedient. Unable to present sufficient evidence of a mutiny, the prosecution changed tactics mid-trial and attempted to prove the sailors were guilty of "conspiracy to commit mutiny." This downgraded charge served as an acknowledgment that a mutiny had not occurred, however prosecution would continue their efforts, attempting to prove the sailors planned to eventually attempt a mutiny.

Proving collective conspiracy to commit mutiny would theoretically require reasonable evidence of an agreement or plan to commit mutiny and proof of each individual defendant's participation. This requires showing direct evidence of private conversations and alleged agreements, but no such evidence was provided. Making the task more difficult, was Naval leadership's inability to match the faces of the sailors to specific actions or events. Sailors testified that commanders never gave them direct orders to load munitions, only asked them questions about their willingness to perform the duties. A petty officer backed up the sailors' claims, saying he had never heard his division officer give the men an order to load ammunition. When the sailors' lead attorney asked a Naval commander if he could identify any of the fifty men he gave an order to, he replied, "No, I cannot."

In a flagrant violation of the sailors' rights to a fair trial, judges allowed the prosecution to submit unsubstantiated hearsay evidence and confessions coerced under duress. Meanwhile, the defense was not allowed to submit evidence of actions taken by leadership which violated federal safety code and Navy regulations. As Port Chicago Sailor Joseph Small once said:

- "That's why I always knew that the verdict was mandatory. The Navy was coming up with it regardless of what was brought out during the trial or what testimony was brought out, or who was found to be guilty of what. The verdict would have been the same. Not because the verdict would have been justified, but because it was the only way to save face."

Sailor Albert Williams similarly felt the outcome was pre-determined. He took issue with the lack of due process, particularly that no matter what each individual sailor said at trial, the verdict would be applied to the entire group:

- "We knew we were all being punished. That's what the atmosphere was there. No matter what you say, you're gonna get this whippin'. Whether you're right or wrong."

The defense attorney for the sailors, Lieutenant Gerald Veltmann, shared the belief that the outcome was pre-determined:

- "I thought, towards the latter part of the trial, that there was a bent to find these people guilty. It was evident. If you sit and participate in it and listen to it for 28 days, you get a pretty strong feeling about the final outcome of it. And I'd already had the remark that Admiral Osterhaus (who presided over the courtroom) made that 'We're going to find them guilty.' So what could you expect?"

On October 24, 1944, after six weeks and 32 days of proceedings, the 7-member jury, comprised of Admiral Osterhaus and six high-ranking Navy officers, would need to arrive at a verdict. There was insufficient evidence of a mutiny, insufficient evident there was a plot to eventually attempt mutiny, and insufficient evidence that the sailors present in the courtroom were ever given a direct order at all. Nevertheless, the Naval jury deliberated for 80 minutes over lunch – which amounts to about 96 seconds deliberation per sailor – before delivering their verdict. The men were pronounced guilty of "conspiracy to commit mutiny" and were all sentenced to 15 years of prison and hard labor, reduction of rank to Seaman Apprentice, and a dishonorable discharge.

NAACP's Thurgood Marshall blasted the Navy for their verdict, saying the sailors were tried "only because of their race and color." He also criticized the military's tendency to accuse Black Americans of mutiny, stating, "I can't understand why whenever more than one Negro disobeys an order, it is mutiny."

Thurgood Marshall and the Desegregation of the Navy

Immediately following the Port Chicago disaster, the public began questioning why only Black Americans were handling high explosives on the evening of the explosions. As a result, on August 12, before the mutiny trial and just one day after the sailors were released from the prison barge, an internal document marked “confidential” was sent from Navy leadership to Mare Island command stated, "There are no divisions of White enlisted personnel performing similar [high explosives] work at the Naval Ammunition Depot or the Naval Magazine" and so "Pains must be taken to insure that there is no justification for an opinion that any type of hazardous work is assigned exclusively to negro personnel." Upon receipt of this directive, White sailors were quickly assigned to load munitions at Mare Island to create the appearance that race was not a factor in assignments at Port Chicago.

Privately, Port Chicago leadership faced criticism for their decisions, and had to answer to the Navy for their unusually rigid enforcement of Jim Crow segregation. In response to this criticism, a member of Port Chicago leadership responded on August 13, 1944 that reports of racial discrimination at Port Chicago and Mare Island were “purely imagined” by the African American sailors.

Despite Port Chicago leadership's belief that they did not discriminate based on race, they would need to take substantial steps to counteract the public perception that Jim Crow segregation was inherently discriminatory and Port Chicago leadership enforced those policies to a "vicious" degree. On October 26, two days after the Port Chicago 50 were convicted, the Admiral who had threatened hundreds of Black sailors with execution just weeks prior issued long-overdue medals to five Black Port Chicago sailors. The medals were awarded for heroic conduct during the disaster and "unselfish devotion to duty."

Despite the act of goodwill, the medal ceremony did little to quell public outcry. Throughout the mutiny trial, Black and liberal publications questioned the Navy's unfair treatment of the Black sailors. This opened the Navy up to further scrutiny for its policies of racial segregation, as many Americans were unaware that segregation was being so strictly enforced, particularly in states like California where Jim Crow segregation was outlawed. These publications focused on the unethical treatment the sailors were subjected to because of the color of their skin. For many, the post-traumatic stress the sailors were experiencing after the disaster and cleanup was understandable. Many believed the sailors' requests to be reassigned to alternative duties following the disaster was a reasonable request and should have been granted. This viewpoint gained traction, particularly because during the trial, both the defense and prosecution made the case the sailors were ill-prepared for the assignment at hand.

The Port Chicago disaster and mutiny trial had laid bare the depth of racial inequality within the Navy during World War II. Under heightened scrutiny, Naval leadership understood the need to take steps to avoid future incidents like the one at Port Chicago. They concluded the Port Chicago protest could have been handled better, and so in extreme cases naval command should be encouraged to assign Black sailors to alternative assignments, even if that means serving alongside White sailors. As a result, on October 9, 1944, while the mutiny trial was still being conducted, the Navy's Bureau of Personnel released a directive titled "Negro Enlisted Personnel - Abolishment of Restrictions on the Assignment Of" which lifted restrictions for Black American assignments where "personnel problems" were present:

-

"In order to enable overall commands to deal successfully with personnel problems brought about by changing conditions and needs, authority is hereby granted addressees to assign Negroes under their cognizance to such activities, and in such numbers, as they see fit."

The racial integration of the Navy had officially begun, and it was in direct response to the protest of the Port Chicago sailors.

For Black American military personnel around the world, the mutiny trial and verdict had a profound effect. It reinforced the perception that Black lives were not valued by the military, and it resulted in morale dropping to new lows. In the months following the verdict, resentment and frustrations with racially-discriminatory policies led to acts of protest throughout the military. These acts of protest included a race riot in Guam in December 1944, a hunger strike of 1000 Navy Seabees in Port Hueneme in March 1945, and the Freeman Field "Mutiny" of April 1945 in which Black airmen refused to leave an all-White officers club.

The case of the Port Chicago sailors began to serve as an example of everything that was wrong with racial segregation in the military. The Navy's mistreatment of the sailors was being written about and published across the country, and it didn't sit well with many Americans, including military leadership.

Many in the Navy were becoming convinced that segregating enlisted men by race was no longer viable, and integrating personnel only under extreme circumstances was simply not enough. Some believed integration was good for national morale and harmony, while others believed all-Black divisions needed to end because they increased the potential for collective action and protest. Regardless of the reason, there was agreement on what needed to be done, and plans to fully integrate the Navy were underway.

In the months following the verdict, the NAACP publicly advocated for the Port Chicago 50 to be released from prison with their widely-distributed Mutiny pamphlet. The NAACP distributed the pamphlet far and wide, including to the Secretary of the Navy, and to First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt who supported the campaign to have the men released. Letters from hundreds of organizations were calling for justice for the Port Chicago 50 while organized drives were being held to sign petitions to demand a retrial, with signatories numbering in the tens of thousands.

In April 1945, on behalf of the fifty sailors, Thurgood Marshall submitted an appeal brief directly to the Navy's Judge Advocate General's Office in Washington DC. He made the case that there was hearsay evidence allowed during the trial and, even by the Navy's own standards for insubordination, the sailors should not have been sentenced to prison. He also accused a prosecutor of racism for singling out sailors from northern states as being troublemakers and more inclined to create a conspiracy. In Marshall's statement to the Judge Advocate he wrote:

-

"I was never so convinced that the evidence was insufficient in a case as I was in listening to that case."

After some consideration, the Navy agreed with Marshall that hearsay evidence should not have been allowed and charges of mutiny may have been overblown. The Navy found that the Judge Advocate, on forty separate occasions, introduced hearsay testimony in an attempt to prove mutiny. On May 17th, due to Thurgood Marshall's appeal, the Navy sent a memorandum ordering Admiral Osterhaus to reconvene his court and reconsider the sentences. The memorandum read:

-

"The admission in evidence of the testimony was in error... and therefore should have been stricken by the court from the record... the court will reconsider whether the prosecution had proven beyond a reasonable doubt... the existence of the specific intent to usurp, subvert, or override superior military authority.... Simple violence or disobedience of orders... is not mutiny."

On June 12, 1945, the Osterhaus court met for a total of 5 hours, and declared it would not change its findings. In the announcement, Secretary Forrestal defended the decision, writing, "The trials were conducted fairly and impartially... Racial discrimination was guarded against."

Marshall strongly opposed this outcome. He requested to meet with the Secretary of the Navy in person, but his request was denied.

On October 6, 1945, just 117 days after Marshall's appeal was rejected, a private letter from the sailors' corrections facility revealed the Navy planned to reverse their decision to imprison the Port Chicago 50, but without giving "credit" to "civilian organizations" like NAACP and other Black organizations for their advocacy efforts. The letter, however, cited this public advocacy, and the resulting public perception, as a factor in their decision to release the sailors:

-

"Considering the amount of publicity and the various civilian organizations who have been receiving credit for efforts in their behalf, I feel that this is a Navy problem and it will be the Navy who is giving them this opportunity to rehabilitate themselves.... and with the various groups of civilians trying to make [the Port Chicago 50] look like martyrs it would be to the Navy's benefit to disperse them and then announce formally from your office that they are back in circulation and doing a job 'out there'."

Thurgood Marshall's tireless legal efforts and public advocacy, along with support from Eleanor Roosevelt, countless Black organizations, and thousands who signed petitions, was a success. On January 9, 1946, the sailors' were granted clemency and they were discreetly released from prison.

Rather than allow the sailors to go home and reunite with their families, the Navy mandated the young men accept the "opportunity to complete their enlistments" serving the Navy overseas performing menial tasks like sweeping and picking up trash.

Joe Small recalls being released from prison:

-

"The Black community had raised such a stink about the case – Thurgood Marshall, Walter White of the NAACP, the Black papers. They brought so much adverse publicity against the Navy until they rescinded the fifteen-year sentence with a dishonorable discharge.

"After sixteen months, all of a sudden, without any forewarning, they told us to pack our bags. You're shippin' out... When they found out we were the Port Chicago guys, everybody sympathized with our position. The White guys. When they heard what we'd been through, they said they'd have done the same thing."

Sailor Freddie Meeks later said, "If it hadn't have been for Thurgood Marshall, I don't know what would have happened. He got them to put us back on duty."

Marshall requested to review the final judgment for the sailors, but the decision to release them was not documented. "The conclusion of that case was extremely interesting," said Marshall, "because there was no official notice of what happened. The records of the final disposition were never entered... [and] there's no record in the Navy Department about it."

Just one month after they were released from prison, in February 1946, following intense public pressure initiated by the Port Chicago protest, subsequent protests, and a public appeal campaign, the Navy became the first branch of the military to end racial segregation.

Two years later, the remaining branches of the U.S. Armed Forces integrated.

The 1994 Navy Review

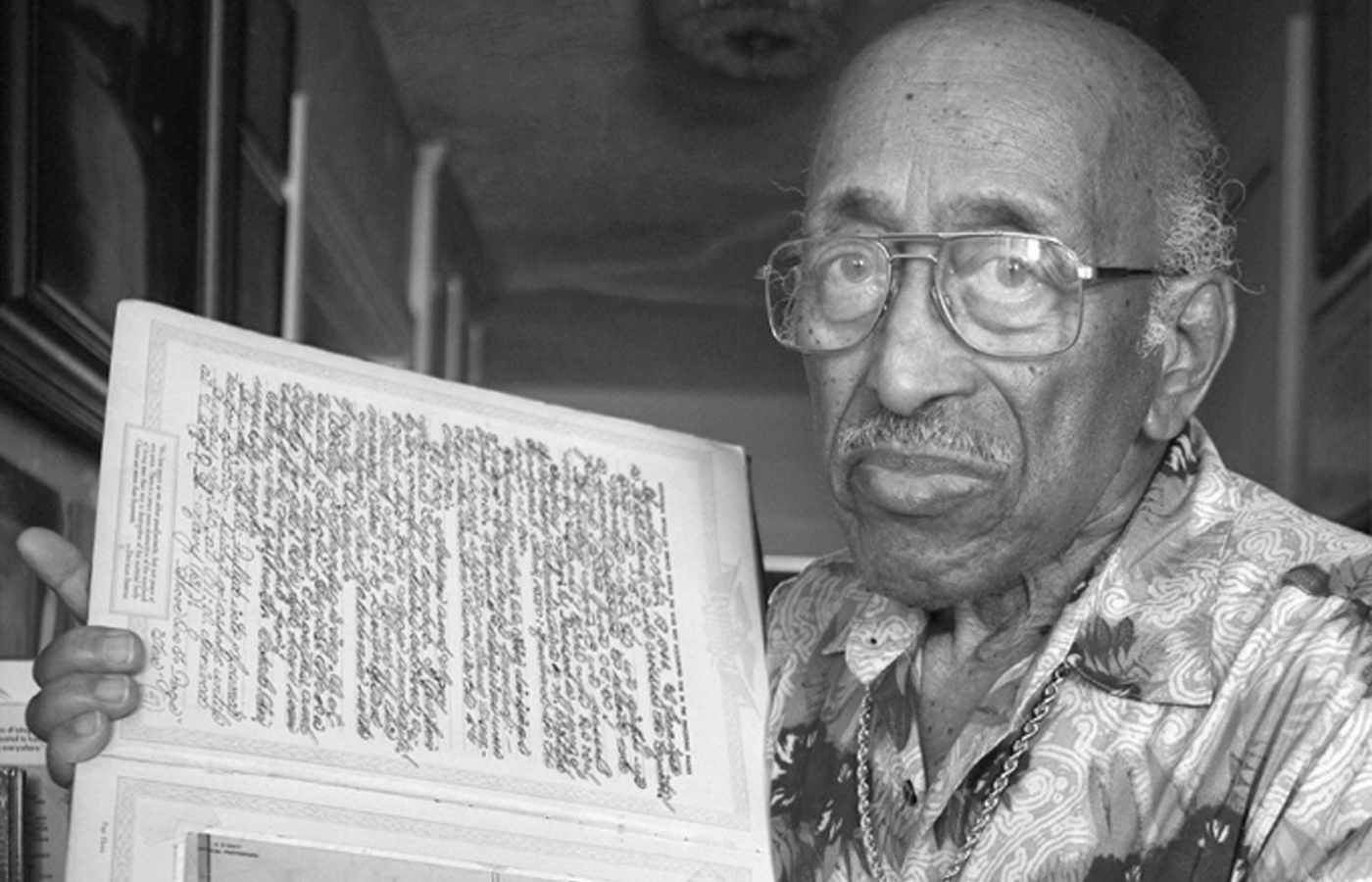

45 years later, in 1989, Dr. Robert Allen's definitive book "The Port Chicago Mutiny" was released. Allen had spent many years researching the subject and traveling the country interviewing the Port Chicago sailors to hear their stories. Prior to these interviews, several of the sailors had never mentioned their mutiny convictions, even to family members, either because they carried personal shame or were worried they would lose their jobs or pensions if their convictions came to light.

With the released of the book, people were hearing the full history of Port Chicago for the first time. Many felt the sailors were unfairly treated and wrongfully convicted. Advocates like Allen, Reverend Diana McDaniel, and Sandra Evers-Manly were joined by lawmakers Rep. George Miller, Rep. Nancy Pelosi, Rep. Pete Stark, Rep. Ron Dellums, Senator Dianne Feinstein, and Senator Barbara Boxer in urging the Navy to re-examine the mutiny case. In a letter to President Bill Clinton, the legislators wrote:

-

"We should put this sorry chapter in racial relations behind us, and allow these remaining men to complete their lives knowing that they have the esteem and regard of their countrymen for their service during World War II."

Representative George Miller, who led the drive to expunge the convictions from the sailors' records, said the fifty men were the victims of bigotry and were unjustly found guilty.

-

"The court-martials would never have occurred if not for the issue of race. These men have lived with this scar on their record throughout their lives. They have been viewed as having less than honorable service, which they clearly did not."

In 1992, after much advocacy from supporters – including high-profile entertainers Morgan Freeman, Harry Belafonte, Danny Glover, and Louis Gossett Jr. – the Navy agreed to "examine all aspects of the allegations of racial prejudice and discrimination." Following a two-year review, the Navy's final report acknowledged the trial was deliberately tilted in favor of the Navy, by stating, "the standard of review in courts-martial in 1944... was to consider the evidence in the light most favorable to the prosecution."

The Navy's report confirmed that "racial discrimination did play a part in the assignment of African-American sailors to load munition," but, according to the Navy's Board for Correction of Naval Records, assignments were the only aspect of Naval life that was affected by racial discrimination. The report concluded that "neither racial prejudice nor other improper factors tainted the original investigations and trials" and "no error or injustice occurred."

At the time, one of the Port Chicago survivors said the Navy's ruling was "like saying its raining everywhere but right here." Port Chicago Sailor Harry Belafonte said "The Port Chicago mutiny was one of America's ugliest miscarriages of justice and a national disgrace. Those sailors were court-martialed... because they'd dared to stand up to blatant institutional racism."

Advocates continued to make the case that policies of racial segregation didn't just affect working assignments, but normalized racial discrimination throughout the Navy and encouraged behavior that devalued Black sailors. They maintained that documented racial prejudice and bias tainted the original investigation, the mutiny charges, and the mutiny trial.

In light of the Navy's most recent judgment, several sailors expressed contentment in their unwavering commitment to their principles.

- Sailor Albert Williams: "I think it was right. I don't know how heroic it is but it was right."

- Sailor Freddie Meeks: "We can figure we was heroes because we stood up for our rights."

- Sailor Joseph Small: "I have never felt ashamed of the decisions I made... I was fighting for something. And if you would ask me to put a name on it, I don't know. But things were not right and it was my desire to make things right."

Repairing the Sailors' Legacies

Unrelenting in their goal to bring the sailors of Port Chicago justice, advocates next approached the sailors with the idea of requesting pardons from the President of the United States. Many of the sailors turned it down, as pardons do not expunge convictions, and are therefore largely a symbolic gesture. On that subject, Port Chicago Sailor Joseph Small once said, "We don't want a pardon because that means, 'You're guilty, but we forgive you.' We want the decisions set aside and reimbursement of lost pay."

By 1999, 47 of the 50 sailors had passed away. As one of the last three survivors, Sailor Freddie Meeks believed seeking a presidential pardon would be a meaningful and lasting way to set the record straight and bring public attention to this little-known history. "After all these years, the world should know what happened at Port Chicago," he said. In December 1999, President Bill Clinton honored the Port Chicago 50 by granting Freddie Meeks a presidential pardon. The remaining two living sailors declined, with Sailor Jack Crittenden explaining that he refused to ask forgiveness for a crime he didn't commit.

Today, the sailors have all passed away, yet efforts to seek justice for their legacies continue. Naval historians now say the heroic actions of the fifty sailors probably prevented another disaster and likely saved lives. Acknowledging the racism the sailors experienced, President Barack Obama once wrote, "Faced with tremendous obstacles, they fought on two fronts – for freedom abroad and equality at home."

A growing chorus of Americans believe our nation owes the Port Chicago Sailors a debt of gratitude for their critical role in winnning the war and for drawing attention to issues of racial inequality within the Navy and American society at large.

Commemorating and Celebrating the Sailors

The Port Chicago Sailors are now being honored and celebrated as heroes in schools, parks, and public institutions.

In 1990, U.S. Representative George Miller began championing the history of Port Chicago and working to overturn the wrongful convictions of the Port Chicago 50. In 1992, through the dedicated efforts of the Port Chicago Committee, now formally known as Friends of Port Chicago National Memorial, Miller successfully advocated to establish the Port Chicago Naval Magazine National Memorial at the site of the disaster. Their efforts were responsible for the presidential pardon of Sailor Freddie Meeks in 1999.

In 2009, President Barrack Obama signed a bill introduced by Representative Miller and championed by Senator Barbara Boxer establishing the National Memorial as a unit of the National Park Service. This act served to honor the lives of the brave sailors who perished in the disaster and those who fought for racial equality at great personal cost.

In 2015, Secretary of the Navy wrote, "The Navy strongly supports pardons or other executive action on behalf of the Sailors so long as those actions do not adversely impact the integrity of the military justice process."

In 2021, the East Bay Regional Park District, the largest park district in the country, named a regional park in honor of Thurgood Marshall and the Port Chicago 50. The 2,540-acre Thurgood Marshall Regional Park - Home of the Port Chicago 50 in Concord, California, honors the Sailors’ bravery and recognizes Marshall’s pivotal role in bringing national attention to their protest and helping lay the groundwork for the desegregation of the U.S. Navy.

In 2022, momentum accelerated. On June 20, the California State Legislature approved SJR-15, authored by Senator Steve Glazer, formally urging exoneration of the Sailors. In July, Congressmembers Mark DeSaulnier and Barbara Lee continued their ongoing push for justice by securing passage of a measure in the House of Representatives, also calling for exoneration, and further advancing the path forward.

Building on these legislative victories, the newly established Port Chicago Alliance (PCA) joined forces with cities, community leaders, and partners to carry the momentum forward.

Over the next two years, PCA used these measures to rally public support — working with Bay Area cities and national groups to pass resolutions, gathering letters of support from leaders and advocacy networks, and presenting them directly to the Navy through coordinated calls and outreach, sending a clear and unified message that the time had come for the exoneration of the Port Chicago 50.

In 2023, on the 79th anniversary of the Port Chicago Protest, the Contra Costa County Bar Association Port Chicago Task Force, an advocacy group comprised of attorneys and community members advocating for exoneration, submitted a legal argument to the Navy outlining why the Port Chicago 50 were legally innocent and therefore wrongly convicted. Their evidence centered around illegal working conditions, errors in the 1944 inquiry, denial of due process, and blatant racial prejudice which tainted the trial and investigation.

These sustained advocacy efforts — from grassroots organizing and municipal resolutions to formal legal arguments — reached their historic culmination on July 17, 2024, when the U.S. Navy officially exonerated the Port Chicago 50.

At long last, the Port Chicago 50, along with the courageous Sailors who gave their lives at Port Chicago Naval Magazine, are honored not only for their sacrifice but for their enduring role in shaping our nation’s pursuit of freedom, civil rights, and racial justice. Their courage, their resistance, and their story now stand immortal, a beacon of conscience and justice for generations to come. ⋆